[Sold at RM Auctions’ sale in Santa Monica, California on May 25, 2002 for $100,000 hammer, $115,000 with buyer’s commission (15% on parts). © 2002 by the author and RM Auctions, Inc. and used with permission.]

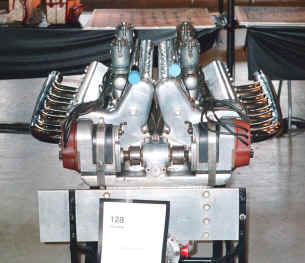

1932 Miller V-16 Engine

When Harry Miller had an idea and couldn’t find a client to finance it right away he would, if means allowed, undertake it himself. So it was with E.L. Cord’s L29 Front Drive. Miller licensed his front wheel drive patents to Cord, for which Miller was paid with royalties and his very own L29 Brougham, a fine automobile in its own right.

For Miller, however, the Lycoming-built cast iron straight eight could have been nothing more than dogfood. Reasonably powerful and reliable, it didn’t fit the Miller image of lightweight, powerful, beautifully-finished, intricate engines even if it did utilize front wheel drive. In the depths of the Great Depression Harry, who always had faith in his ability to come up with another brilliant idea and someone to finance it, embarked upon design and construction of an automobile that would, had he possessed more than a scintilla of business acumen, have made the Model J Duesenberg an exercise in plebian excess.

Miller’s concept was a 303.6 cubic inch V-16 with dual overhead camshafts on each bank and a 45º vee angle. The cams operated two valves per cylinder with siamesed downdraft intake ports in the camshaft valley. A dry sump system lubricated its mechanical intricacy. Block dimensions were taken from Miller’s overbored 122 straight eights and the crankcase design was Miller’s reliable and proven aluminum barrel with inserted diaphragm main bearing carriers.

Harry Miller appreciated the difference between racing engines and those in passenger cars. Gear whine was anathema, so he directed the creation of a camshaft drive system of crankwheels and eccentric rods to do away with gears. Leo Goosen was still working at Schofield-Miller so the design of the engine and its intricate four-cam drive system fell to Miller’s nephew Walter Steele. The Miller-Cord may have had problems, but they were not with Steele’s design work. Miller also came up with a gifted mechanical braking system that employed eighteen radial rods within the brake shoe to transmit uniform pressure throughout a full 360º to the drum. Harry may have lost his sense of commercial balance with this grandiose project which no one could (or would be willing to admit they could) afford in the Depression. But he’d lost nothing of his vision and insight.

Miller’s front wheel drive system had one implacable weakness, however, a weakness exacerbated by the power and torque of the 303 V-16. In Miller’s design the 3-speed gearbox was placed after the rear axle reduction gears, multiplying torque through the gearbox. The Miller 91 front drives were virtually impossible to shift under power. S.C. Chesterfield, who designed the front-drive system for the Miller-Cord, resolved most of the shifting problem but in its first test drive the 250 horsepower Miller-Cord V-16 stripped both 2nd and 3rd gears climbing a hill.

Shortly thereafter the 303 V-16 disappeared from Harry’s Cord L29. All evidence points to it being reconstructed and used in Miller’s 1931-32 V-16 Indianapolis race car.

The V-16 Indy Car

The Big Eight rear wheel drive chassis built in 1931 were large enough (by design?) to accept the 303 V-16 and one was so used by Harry Miller. The engine out of the Miller-Cord L29 benefited from a few racing oriented changes including gear train drive to replace the crankwheel and eccentric shaft cam drive and relocation of the accessory drive. Shorty Canton drove it but managed only 27th place. This Miller Indy story ends here, however Harry came back in ’32, doing himself one better (at least in driven axles) with a four-wheel drive. He once again brought a new patron to the party.

The 308 V-8 4WD Indy Cars

Miller had developed both rear wheel drive and front wheel drive chassis to high degrees of effectiveness. Having resolved both those idioms he proceeded to the next logical step, at least for Harry Miller, by combining the two into an unbeatable (on paper) leviathan. The four-wheel drive Miller appeared at Indy in 1932, even as Harry A. Miller, Inc. was on its last legs. Leo Goosen laid out an innovative V-8 with 45º vee-angle, four overhead camshafts, a “flat” (180º) crankshaft and, new to Miller practice, a split aluminum crankcase with babbited main bearings in removable caps. The cylinder blocks, however, were still iron, cast in unit with the heads. The chassis was immaculately finished and presented as always for a Miller and utilized the parallel quarter elliptic leaf springs of the Big Eights with deDion axles front and rear. Drive from the 308 cubic inch V8 came through a Miller 3-speed gearbox to a center differential from which power was distributed to the front and rear axles.

Two cars were built. One was bought by the Four Wheel Drive Auto Company in Clintonville, Wisconsin, an established builder of four-wheel drive vehicles for heavy trucks, construction and military applications, and raced at Indy in 1932 as the Miller FWD Special. The other was Miller’s entry, sponsored by William A.M. Burden, a wealthy New Yorker, which raced as the Harry Miller Special.

William A.M. Burden

Bill Burden’s great-grandfather was Cornelius Vanderbilt. He was fascinated by automobiles at an early age, exercising his “Red Bug” on the family estate at Mt. Kisco, New York and captivated when his Aunt Ruth let him drive her Mercedes in Newport, Rhode Island. He eventually owned fifty-three automobiles, one of them Harry Miller’s four-wheel drive V-16 road car and was one of the principal organizers of the 1936 and 1937 Vanderbilt Cup races at Roosevelt Field on Long Island. Burden took on important government roles under Roosevelt including persuading South American governments in the days before WWII to deny flying privileges to Italian and German airliners which were communicating shipping information to German U-boats. He was Eisenhower’s Ambassador to Belgium during the Congo rebellion. A founder of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, he later persuaded President Nixon to establish the Smithsonian Institution’s Air and Space Museum where today the drawings and notebooks of Leo Goosen are preserved, complementing the Leon Duray/Ettore Bugatti Miller 91 Packard Cable Special in the Smithsonian’s museum of American history.

Harry Miller somehow convinced Bill Burden to sponsor Miller’s 1932 Indianapolis entry for the 303 V-8 four-wheel drive car driven by Gus Schrader. The Miller wrecked on the seventh lap but Miller had already succeeded in getting Burden track privileges before the 500. He turned a lap at a reported (by Miller) 107 miles per hour. Then he went home before the race – apparently (and rightly) not very impressed by the four-wheel drive Miller’s prospects.

Nevertheless Harry Miller, who must have been some smooth talker when it mattered, convinced Burden that he should purchase a fantastic four-wheel drive supercharged V-16 powered Miller road car. The agreed price was $35,000. 1932 was in the pit of the Depression. The most expensive cataloged 1932 Cadillac V-16 cost $6,000 with a Limousine Brougham body.

Dapper Harry Miller was more than a dreamer, more than an intuitive automobile designer. Harry was a salesman.

The Burden V-16 Four-Wheel Drive Passenger Car

Not satisfied with the naturally-aspirated 303 V-16, Harry Miller’s proposal to Bill Burden specified a supercharged version with 500 horsepower and a sleek boat-tailed speedster body on a 130″ wheelbase. Goosen drew up and Fred Offenhauser had cast new blocks. The Roots-type positive displacement supercharger was located at the rear of the engine, interposed between it and the clutch, an unprecedented (and typically Harry Miller) innovation. DeDion axles were used front and rear, sprung from the parallel quarter-elliptic leaf springs that were then Harry Miller’s favorite. The engine nestled between massive, but flexible, chassis side rails well below the hood’s peak and the car’s monumental frontal aspect carried the ribs of its immense front-drive housing through into the vee radiator cowl. As completed, William Burden’s Miller V-16 speedster had cycle fenders that were less complementary to Emil Deidt’s bodywork than the clamshell design originally proposed, but it still justified the description, “awesome.”

William Burden’s brother Shirley was then working in Los Angeles at RKO Pictures and William seconded him to inspect the slow progress at Miller’s. Burden’s autobiography, “Peggy and I” quotes the priceless contemporary observations of his brother:

“I was courting (in the old-fashioned way) a wonderful girl I had met on a blind date, Flobelle Fairbanks, the niece of Douglas Fairbanks….

“[William] reminded me of what he had ordered: a car of sixteen cylinders, four-wheel drive, 500 horsepower, supercharged. [He asked] me to go to the factory to see what was going on…. I visualized a small garage with a couple of greasy mechanics sweating over an engine block with holes in it … but the factory – and it was a factory in every sense of the word – took up at least three-quarters of a city block. Inside we met Fred Offenhauser, a charming gentleman in a white coat….

“The shop was filled with every kind of machine … At each machine was a mechanic working on a small shiny something. Later – much later – when the trip through the plant was drawing to a close, … I got up enough courage to ask Offenhauser where the car was. He explained in a tolerant voice we had seen the car. All those shiny somethings when assembled would make one gorgeous Miller Special….

“The conclusions were obvious. These men were artists. Money was no object, especially when it belonged to someone else. If you wanted the car badly enough, you had to pay up on their terms. It was hard explaining this to my brother. I think he understood.

“A lot of time and a lot of money later, the Miller Special was finally finished. The torpedo-shaped body was painted black. It had two rather uncomfortable bucket seats, a low windshield, and no top. The engine, which seemed to take up at least three-quarters of the length of the car, was a joy to behold. Whether it ran or not mattered little. It should have been in a museum.

“My romance with Flobelle was progressing, so I decided to take her for the first ride. It was summer. Large picture hats and diaphanous flower print dresses were in. There were very few houses on Cold Water Canyon Road in Los Angeles in those days. The grade was gentle and led to a beautiful view of the San Fernando Valley at the top. I decided to take her there.

“Flobelle was a sight to behold as she floated down the steps to Bill’s black Miller Special chariot. The picture hat, the flower print dress, that beautiful blonde hair, and that face, that face – that wonderful face…. I drove rather conservatively at first; I wanted to get the feel of the car. When we reached Cold Water Canyon I could not resist bearing down a little harder on the accelerator. The car leapt forward as a true thoroughbred should. Flobe was getting a bit edgy. She didn’t seem to understand why we had to go so fast even when I explained to her in a loud voice that I had to test the car in order to give my brother a full report of its performance.

“I think we were going around eighty when it happened. There was a roar –the engine hood flew off and a geyser more spectacular than the one at Yellowstone National Park appeared from nowhere. I would have enjoyed the spectacle more had I not been so busy trying to stop the car. When I finally did, and took stock of the damage, I was speechless. Flobe, on the other hand, was not. She did everything but break off our engagement. Her picture hat was ruined – her dress was ruined – her shoes were ruined – her hair was a mess. I didn’t look so good either, but that was my problem.

“Several weeks later Mr. Offenhauser telephoned and apologized for the accident. He said there was nothing wrong with the car; the radiator needed adjusting.

“I didn’t drive the Miller Special much after that. I was too busy trying to get back in my future wife’s good graces…. but several months later a bird perched on my window ledge and told me when they finished building the engine it was too big to fit into the chassis, so they had to cut down the size of the radiator and the cooling fan. Result: there was not enough water to cool the engine.

“Well – it made beautiful geysers, and gave work to twenty-five mechanics for a very long time.”

William Burden took delivery of his Miller V-16 Four-Wheel Drive but never felt comfortable with its handling, brakes or even its power. He sold it for $400 in 1937 or so. Yet, despite William Burden’s disappointment with Harry Miller’s four-wheel drive V-16 passenger car the siren song of Miller’s vision played in Burden’s ears and he continued to consult Miller for concepts of automobiles, speed boats and aircraft in years to come.

The buyer of Burden’s V-16 Miller turned out to be an intermediary for none other than Harry Miller, then working on the Gulf-Miller cars. Leo Goosen produced an August 1938 drawing for a 3⅛” stroke V-16 crankshaft, exactly the dimension needed to create an Indy-spec naturally-aspirated 270 cubic inch V-16, but it was apparently never built.

Following Harry Miller’s death in 1943 Louis Rassey bought an assortment of V-16 parts from Miller’s estate and from them created a naturally-aspirated 272 cubic inch downdraft port V-16 which went into an early Miller front-drive chassis – maybe as early as 1929. Shorty Cantlon drove it at Indianapolis in 1947 (sixteen years after pedaling Miller’s V-16 at Indy in 1931), qualifying fifth at 121.462 mph. Shorty stalled at the start but after restarting he howled through the field until the 40th lap when Bill Holland, the leader, lost control and pulled back on track in front of Cantlon who swerved to avoid Holland, driving into the wall and dying instantly. In 1948 Louis Durant and Duane Carter couldn’t qualify the Miller V-16 in a different chassis. Rassey observed at the time that the engine was smooth and powerful but was heavy for the chassis in which he raced it. Its performance on the track in Shorty Cantlon’s 1947 charge back into contention after stalling at the start conclusively demonstrates the truth of Rassey’s statement.

Today

Following the 1948 Indianapolis 500 Louis Rassey sold his Miller V-16 which eventually found its way into the extensive collection of Doc Young. While it was there Buster Warke, postwar driver of Louis Meyer’s 1936 Indianapolis-winning Miller and an experienced Miller mechanic, overhauled it. The V-16 has not run since. Jim Brucker acquired it from Doc Young and displayed it for years at his Movieland Cars of the Stars Museum until its acquisition by Richard Freshman.

This is the only V-16 Miller automobile engine in existence with traceable history to Harry Miller’s last experiments in Vee-type engines. It is inextricably linked with Harry Miller’s Miller-Cord L29, the lost William A.M Burden Four-Wheel Drive road car and Lou Rassey’s 1947 V-16 Indianapolis entry driven by Shorty Cantlon.

Mechanically intricate, intrinsically powerful, aesthetically beautiful, there is nothing not to love about Harry Miller’s V-16. As it sits, upon a stand, it is “art.” Fired up on its own it will be “music.” In an original or reproduction chassis it is an on-track “challenge.” In any case it will thrill its owner, and all its onlookers, with its history, its performance, its sound and its legends.

Click here to return to the Catalog Descriptions Index page.

The Miller V-16 is an engineering tour-de-force. I’m not sure of the dates on these posts, but there is no mention of the replica Miller V-16 built up by collector/restorer Chuck Davis. I saw Chuck’s engine running in his Chicago-area shop located near Chuck’s concrete construction business. A beauty to see and hear!

Regards,

Mike Boyajian